Chapter 2 Converting sound to bytes

Chapter keywords: analog-to-digital conversion, digital-to-analog conversion, AD, DA, ADC, DAC, microphone, sound insulation, directional, filtering, sampling, sampling frequency, nyquist frequency, amplitude resolution, quantization, rounding, noise, recording level, gain, clipping, audio formats, codec, lossy, lossless, scale, fade, concatenate, chain, SoundEditor.

2.1 Overview

In order to process sounds by means of a computer program, or telephone, we first need to convert that sound, the variations in air pressure, to numbers that are then further processed by a computer or by a telephone device. This is a two-step process, involving at least two key components in order:

the microphone: this device transforms variations in air pressure into matching variations in an electrical signal. The microphone has a thin membrane, and displacements of the membrane (caused by the sound pressure wave hitting the membrane) are transformed into proportional fluctuations in electric current (Ampere), electric voltage (Volt) or electric resistance (Ohm), depending on the design of the microphone. For instructions about how to handle a microphone, see the text box in §2.2) below. The analog electrical signal is then passed on from the microphone to…

the analog-to-digital-converter (ADC): this device converts a continuous, analog electrical signal into a stream of discrete, digital numbers. The ADC repeatedly measures the input signal, and reports the digital output value of that input signal. This process is also called ‘sampling’. Sampling a signal is done with a certain ‘sampling frequency’ (number of repeated measurements per second) and with a certain precision of measurement (known as ‘amplitude resolution’), both explained below. The result is an output stream of digital numbers (in bytes), to be handled further by computer software (e.g. to be displayed, compressed, transmitted, stored, played back, etc.)13 14

Very soon, whenever you want to hear sound from a computer or from a telephone connection, you will also need

- a digital-to-analog-converter (DAC): this device converts a stream of discrete, digital numbers into a continuous analog electrical signal, with a pre-specified conversion frequency and amplitude precision. The result is an output analog electrical signal, to be handled further by audio hardware (e.g. to be amplified, sent to a loudspeaker, etc.)

2.2 How to handle a microphone

A good microphone is a very sensitive and very expensive device. Treat it with great care. Never blow into a microphone (it’s far better to just say

testorcheckor anything with plosive and fricative consonants). Do not tap on its surface.Do not plug or unplug the microphone into/from a “hot” port. First set the port’s input/output volume to zero, then plug/unplug.

Do not speak into the microphone, but just over it or alongside. The microphone should measure sounds, but not the flow of air coming out of a speaker’s mouth and nose. If the microphone comes with a foam cap to dampen airflow, then use it.

Do not touch the microphone while it is picking up sound; this will result in undesired (and often loud) contact sounds in the output signal.

2.3 Key parameters in AD conversion

The digital signal obtained by analog-to-digital conversion is an approximation of the original (analog) sound. Two key parameters determine the accuracy of the digital approximation, and thus the quality of the digital sound recording. The first parameter is the number of samples taken per second: the sampling frequency, and the second parameter is the number of bits used to describe the amplitude value of the sample: the amplitude resolution. These two parameters are further explained below.

2.3.1 Sampling frequency

The sampling frequency (symbol \(f_s\)) is the frequency with which digital samples are taken and stored from the original analog sound. With a higher sampling frequency, the digital signal better (more closely) approximates the analog source in the time dimension, resulting in a better digital recording. The sampling frequency is expressed in samples per second, in Hertz units (cf. §1.8.1). A sampling frequency of 2 kHz (2000 Hz) means that the sound is sampled \(2000 \times\) per second.

The sampling frequency \(f_s\) must be at least \(2 \times\) the highest frequency \(f\) in the analog source sound. Thus, the source sound may not contain any components with frequencies above \(f_s / 2\), the so-called ‘nyquist frequency’ (this requirement follows from the so-called ‘Nyquist theorem’). In practice this requirement is guaranteed by low-pass filtering the source sound (see §4.2 about filtering), with the nyquist frequency as cutoff, thus removing any components with frequencies higher than the nyquist frequency. This filtering is routinely done before AD conversion, by the AD conversion hardware.

For speech, most acoustic information is contained in the frequency range up to 8 kHz. Given the previous paragraph, this means that we need a sampling frequency of at least 16 kHz15 or higher. In most phonetic projects, the most relevant phonetic information is contained in the frequency range up to 16 kHz, for which a sampling frequency of \(f_s = 32\) kHz16 is adequate. For music, relevant information may be contained in the full audible range up to 22 kHz, and the standard sampling frequency is 44.1 kHz17.

Check the sampling frequency before making a digital recording, set it to an appropriate value, write down the sampling frequency in your lab journal, and mention it in your report.

Using a higher sampling frequencies will result in proportionally larger digital sound files, which require longer processing times and more computer storage.

Aside: In the past, analogue telephones used a limited bandwidth of 300 to 3400 Hz; this allowed low-cost transmission of speech that was still intelligible. Such ‘telephone speech’ may be sampled at \(f_s = 8\ \textrm{kHz}\), capturing acoustic information in the frequency range up to 4 kHz. You may encounter legacy speech recordings sampled at 8 kHz, and/or research reports mentioning this \(f_s\) value.

2.3.2 Amplitude resolution

The amplitude resolution, or quantization, refers to the number of separate steps in amplitude (voltage) that are discerned during sampling. Again, with a higher amplitude resolution, the digital signal better (more closely) approximates the analog source in the amplitude dimension, resulting in a better digital recording. The amplitude resolution is expressed in bits18 or bytes19.

The recorded amplitude values are discrete, and because of the “jump” from one discrete amplitude step to the next-higher or next-lower value, the amplitude values are “rounded” to some extent. This rounding or quantization results in audible noise in the digital signal. This rounding noise amounts to half a step of possible amplitude values. If we have more amplitude values (higher amplitude resolution) then the rounding off becomes less noticeable20.

In phonetics, the most common amplitude resolution is 16 bits, or \(2^{16} = 65536\) different amplitude steps21. The quantization noise has an amplitude of \(1/65636\) of the maximum amplitude; this corresponds to a signal-to-quantization-noise ratio of about 98 dB. This small amount of rounding noise is negligible.

2.4 How to record a sound

For any audio recording, there are a few essential precautions that you’ll need to attend to, in order to obtain high-quality recordings suitable for subsequent analysis, manipulation, and/or presentation.

2.4.1 Remove non-target sounds

In order to obtain a high-quality recording, it helps to attenuate all non-target sounds, in various ways:

- If available, use a sound-attenuating cabin or booth. The booth will help to insulate your target signal from unwanted other sounds. Close the door of the booth properly. Leave non-essential equipment (watches, phones) outside the booth.

If a booth is not available, then find the quietest space available. Try using thick curtains, carpets, and cushions, and other sound-dampening materials, to improve your recording. Make lots of test recordings, listen critically, and attempt phonetic analyses before you proceed with your recordings.

Background: Phonetic analyses typically aim at finding acoustic properties in the speech signal that may be related and relatable to the speaker’s articulations and prosody. However, similar spectral properties (e.g. resonances, formants, see §5.2) may also arise from acoustic reflections in the recording room, and it may be difficult or impossible to disentangle similar spectral properties coming from different origins. Hence it helps to minimize any acoustic reflections in the recording room22.

If there is a lot of noise or non-target speech, try using a directional microphone, which only or mostly picks up sounds coming from one direction, and which attenuates sounds from other directions. Vary the position of the microphone and make test recordings.

A headset microphone is often to be preferred over a microphone on a tripod or handheld. With a headset, the distance from the microphone to the mouth is approximately constant, and interference from background sounds and noise will be minimal. Place the microphone near the corner of the speaker’s mouth, outside the air flowing from the speaker’s mouth and nose.

Switch off any non-essential equipment, and try to attenuate non-target sounds from elsewhere. Even if you cannot hear a difference, the equipment sounds and outside sounds may interfere with the target sound signal, resulting in unwanted artefacts.

Despite all these precautions, outside sounds may still interfere. This happens in particular with low-frequency signals, e.g. due to traffic outside, elevators elsewhere in the building, and so forth. These interfering sounds are typically outside the frequency range of speech. Therefore we can easily remove them, by high-pass filtering the target speech signal, before DA conversion.

- Use a high-pass filter that will discard frequencies below a certain cut-off frequency (see §4.2).

- Set the cut-off frequency well below the lowest possible frequency (component) in your target speech, say, a cutoff frequency of about 50 to 60 Hz.

2.4.2 Check recording level

During your recording, check the level of the recording.

If the recording level is too low, then the target signal is too weak, and the background noise (including quantization noise) is relatively strong. It’s very difficult or impossible to fix the signal-to-noise ratio later, so you need to fix this now, during the recording.

If the recording level is too high, then the loudest portions of the target signal will be too strong, leading to “clipping” or distortion. It is impossible to fix this later, so you need to fix this now, during the recording.

There are several ways to adjust the level of the recording:

- by adjusting the level of the input channel (maybe called Gain), in your computer settings,

- by varying the distance from the sound source to the microphone (in general: the closer the better, but also depending on the type of microphone),

- in speech: by instructing the speaker to speak more loudly or more softly.

2.4.3 Avoid lossy audio formats

It it tempting to record sounds digitally on smart devices which store lots of audio in compressed (lossy) formats such as MP3 or MP4. However, the lossy compression of audio data may lead to difficulties in subsequent phonetic analyses. The results may sound quite right to your ears, but details in timing or in spectral details may nevertheless have been lost in the compression. It depends on your interests and your research questions whether or not this constitutes a problem. For phonetic research, it is generally better to record in ‘lossless’ audio formats that do not compress the audio data, rather than in ‘lossy’ formats. Check whether and how your smart device can make lossless recordings: if possible at all, this will probably require a deep dive into the settings on the recording device.

For the same reason, it is better to use a cable connection between the microphone and the computer, and not a wireless (Bluetooth) connection. The Bluetooth compression will negatively affect the quality of the recording. Consequently, wireless headsets are also to be avoided as microphones.

2.4.4 On your computer, using Praat

We assume that you use a computer equipped with a microphone, or with an analog input port for an analog signal coming from an external microphone. If using an external microphone, plug it into your computer (see §2.2). Check that audio input is arriving in your computer, using your computer system settings for sound input (if using an external microphone, select the appropriate channel).

There is a helpful option in Praat, from the main menu (not from the Objects window menu): Praat > Settings > Sound recording settings... where you may adjust certain settings as needed.

2.4.4.1 Record

In the

PraatObjects window, selectNew > Record mono sound. In most situations it is not necessary to record stereo sounds. This will open theSoundRecordertool within Praat.Choose the appropriate sampling frequency, e.g. 22050 Hz (see §2.3.1). You may receive an error message if the chosen sampling frequency is incompatible with your computer.

Click

Record, and speak a test sentence into the microphone, or make a test recording of your talker, or other sound source.

See §2.6 for ideas about what you, or your test talker, might say for the recording.

After making a test recording, clickStop.While recording, check the level of the recording (§2.4.2).

InPraat, make sure that your recording level is in the yellow zone, with occasional peaks in the red zone, but without clipping.Click

Playto listen to your recording. Repeat the recording until the recording level is good.Enter a name for the recording, e.g.

river, in the lower right corner (this name will be used withinPraat).Save the recording:

Save to list(i.e., to the list of objects in thePraatObjects window).

Your speech recording is now an object within Praat.

2.4.4.2 Save

For storage, you should save this object as an audio file on your computer’s hard disk.

To do so, in the

Praatobject window, select the Sound object that you just recorded. (Normally this new object has been added at the BOTTOM of the list of objects).From the top menu, choose

Save > Write to WAV file...or choose any of the other audio formats. Save the Sound object in a folder and under an unambiguous name that you will remember and understand a year from now – not justriver.wav. Note in your journal the folder and filename of your sound recording. Keep projects in separate folders on your computer.

2.5 How to play back a digital sound

Once again, we assume that you use a computer equipped with an analog output port for playing back sounds. Check that audio output is audible, using your computer system settings for sound output to your loudspeakers or headphones.

There is a helpful option in Praat, from the main menu (not from the Objects window menu): Praat > Settings > Sound playing settings... where you may adjust certain settings as needed.

In the Objects window, select the Sound object(s) that you want to play back. Then press the Play button in the Objects window. You might interrupt the playback with the Esc key, but this depends on your playback settings (see the paragraphs above). (If you have selected multiple Sound objects, then they will be played consecutively, without a pause in between; see §2.7.4.)

2.6 What to say?

What should the human talker (such as yourself, perhaps) say for a speech recording? Appendix A lists some sentences and texts for Dutch and English.

2.7 How to manipulate and edit a digital sound

2.7.1 Scale

Even if you have heeded all the warnings in this chapter, it may be necessary to adjust the amplitude or intensity of your digital recording. Sample values in the digital sound will be multiplied with a certain scale factor. Praat has different recipes to choose this scale factor.

2.7.1.1 Scale amplitude

Modify > Scale peak....

The amplitude scale factor is chosen so that the maximum sample value is a particular proportion \(\times\) the maximum possible amplitude value (which in Praat is \(1\) by definition). Sensible values for this proportion are \(0.99\) (the default) or \(0.995\), resulting in peak values which will be \(0.2\) dB or \(0.1\) dB below the maximum possible amplitude value, respectively. (If you choose a proportion \(>1\), the result will contain clipped samples, with amplitude values exceeding the maximum possible value. This will lead to distorted sound when played back. Do not choose a proportion \(>1\) here.)

2.7.1.2 Scale intensity

Modify > Scale intensity....

The amplitude scale factor is chosen so that the average intensity of the resulting sound is the specified target intensity in dB SPL (see §1.8.3). Praat warns you that the result may contain clipped samples, with amplitude values exceeding the maximum possible value. Such clipped samples will lead to distorted sound when played back.

2.7.2 Excise part of a sound recording

In many projects, we wish to excise (cut out) a part of a recording, and save that part as a separate audio file.

Praat contains a so-called SoundEditor to perform these tasks.

Reliably segmenting or delimiting fragments of a speech utterance requires the background knowledge provided in the following chapters — and practice. Segmenting speech will also be discussed in Chapter 7 on phonetic annotation. Below are some brief starter instructions.

Select an input Sound object in the

PraatObjects window.Choose

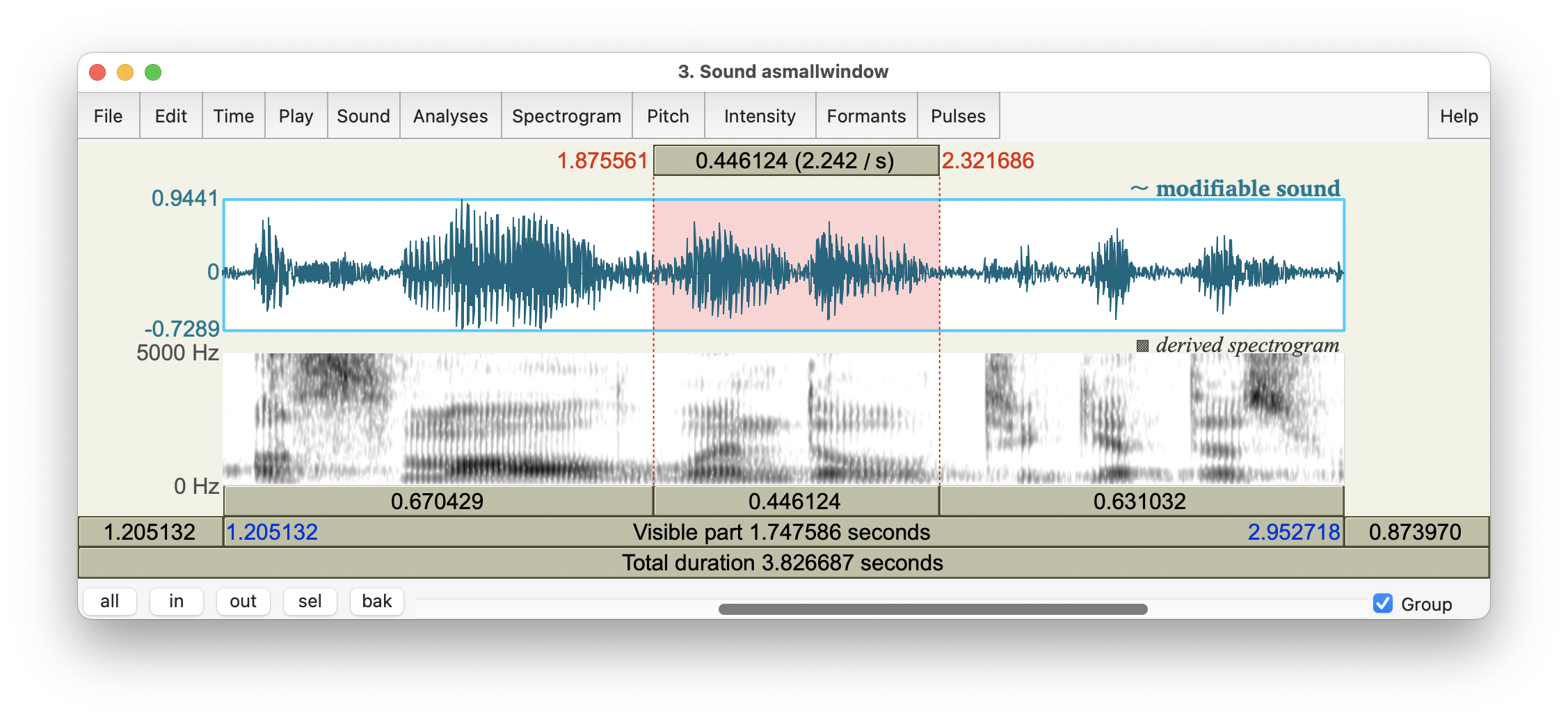

View & Edit. This will open a SoundEditor window. Figure 2.1 shows an example of a SoundEditor, displaying the fragment …a small window to get this… spoken by a male speaker of American English; the single word window is highlighted.

Figure 2.1: SoundEditor window, showing oscillogram and spectrogram of the fragment …a small window to get this…, with the word window highlighted.

The SoundEditor in Fig.2.1 shows a fragment of speech, taken from the audio file named 10-18-17_Council_SLASH_10-18-17_Council_DOT_HD_DOT_mp3_00285.flac from the Peoples Speech corpus at https://huggingface.co/datasets/MLCommons/peoples_speech. For details about that corpus, see Galvez et al. (2021).

The SoundEditor contains a lot of information! In the top panel you always see an oscillogram (§1.6). Below, there may be additional and overlapping visualisations of the Spectrogram (Ch.6), Pitch, Intensity, Formants (§5.2), and/or voice Pulses. These additional visualisations will be discussed later in this tutorial guide; for now, you may switch them off by choosing the appropriate buttons in the top of the SoundEditor window, and then unselecting the Show option.

In the SoundEditor window, you can select a part of the recording with your mouse. The selected area is marked in pink in the oscillogram panel of the SoundEditor window, as shown in Fig.2.1.

You can play back the selected part, or the parts before/after it, by clicking the appropriate buttons (labeled with the durations of those parts). For more information about audio playback from

Praat, consult §2.5 above.In the SoundEditor window, you can use the buttons in the lower left corner to zoom

in,out, to zoom out to the entire sound (all), or to zoom to theselected part.You can also select a part of the recording by specifying the start and end times explicitly: choose

Time > Select...and enter the start and end times.By convention, the selected part should begin and end at positive zero crossings (where the signal changes from negative to positive; see §2.7.3 below). You can find these precise places as follows (disregarding shortcuts in

Praat):- put the cursor in the approximate area where the boundary should be located;

- choose

Sound > Move cursor to nearest zero crossing; - ask

Praatto report the cursor location in its Info window:Time : Get cursor, and note this time; - do this for both start and end of the selection part;

- use these noted times to set the selection part as described above.

In this way, the word window was selected in the SoundEditor in Fig.2.1.

To save the selected part as a separate audio file: in the SoundEditor, choose

File > Save selected sound as WAV file.... Provide the appropriate folder and file name, and clickOK.You may also extract the selected part into a new Sound object in

Praat. In the SoundEditor window, chooseSound > Extract selected sound (preserve times)if you wish to maintain the same times as in your source recording: the new Sound object will have a starting time equal to the starting time of the selection in the source recording. If you want your new Sound to start at zero, then chooseSound > Extract selected sound (time from 0).The new Sound object may need a fade-in and fade-out (see §2.7.3 below).

Remember to save this new Sound object (see §2.4.4.2) if you wish to keep it.

2.7.3 Fades

An abrupt change in amplitude may occur at the beginning and/or at the end of a sound file. Such an abrupt change will be heard as an impulse sound (see §3.3.2), that is, as a clicking sound. This may happen with speech cut out of a longer speech utterance. Due to the workings of the ear, such an impulse may briefly mask subsequent sounds, i.e., affect the perception of subsequent sounds. In order to avoid these artefacts, it is common practice to enforce a gradual fade-in (at the onset, from zero) and fade-out (to zero). This is especially important if you intend to play back the sound to listeners.

These smooth fades can be made in Praat by choosing Modify > Fade in... and Modify > Fade out..., with a fade duration of about 0.005 to 0.010 second. Samples affected by the fade are multiplied with a factor increasing from 0 to 1 during fade-in, or decreasing from 1 to 0 during fade-out.

2.7.4 Concatenate

In phonetic research, we often want to construct a “chain” of sounds in a particular order e.g. (1) a warning beep, (2) a silent portion of fixed duration, and (3) a speech stimulus. This can be achieved in several ways; the most basic operation is to “concatenate”, that is, to create a “chain” of sound objects.

In the Praat Objects window, select the Sound objects in the order in which they are to be concatenated, e.g. (1) beep, (2) silence, (3) stimulus. In order to select multiple Sound objects from the list, in a specified order, press Command while selecting objects.

Then choose Combine > Concatenate in the Objects window. The resulting “chain” of Sounds will be added to the BOTTOM of the list of objects. Remember to save this new Sound object (see §2.4.4.2).

The input signal to be sampled often comes from a microphone, but other signals may also be sampled, e.g. the signal coming from an electro-encephalogram (EEG) electrode.↩︎

In a speaker’s telephone, the stream of numbers (output from the ADC) constitutes the input for subsequent processing and data compression, even before speech data are transmitted to the receiving phone.↩︎

This is the typical sampling frequency in VoIP, “wideband speech”.↩︎

This is the standard sampling frequency for FM radio.↩︎

This is the standard sampling frequency for audio CDs.↩︎

1 bit or binary digit is a single digit in the binary system. A binary digit can only have 2 possible values, \(0\) or \(1\) (just as a decimal digit can have 10 possible values, \(0\) to \(9\)).↩︎

1 byte is 8 bits, or \(2^8=256\) possible values.↩︎

Notice that one bit is required to record the sign of the value (positive or negative), so with 1 byte of resolution we can in principle record 256 possible amplitude values, running from -128 to +128, with rounding noise having an amplitude of \(0.5/128\) or \(1/256\) of the maximum amplitude. This corresponds to a signal-to-quantization-noise ratio of 50 dB. In practice, however, amplitude values are not stored as integer numbers but as floating numbers.↩︎

This is also the standard amplitude resolution for audio CDs.↩︎

Frequency and formant measurements may be suspect if the corresponding wavelength (for frequencies) or wavelength \(\times 4\) or wavelength \(\times 2\) (for formants) corresponds to one of the dimensions of the room (see §1.8.5 and §5.2.3); or if the reported formant frequency is below 200 Hz; or if the reliability of the frequency measurement is low. ↩︎